A Historical Look at Lighting Efficiency

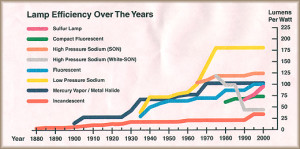

Of particular interest is the astoundingly low efficiency that early technology featured, i.e., how few lumens were made available for each watt of electrical power. 130 years ago, that figure was approximately 1.0, and even today, the efficiency of incandescent light bulbs remains fairly low (the figure is about 16). About 5% of the electric power is converted into light, the remainder of which is dissipated as heat.

All of this is a reminder of an important facet of our progress as a civilization vis-à-vis the use of energy and its environmental impacts in our world today. Energy efficiency remains far and away the greatest opportunity for us to stem the rise of greenhouse gases and toxins into our atmosphere. Our challenge of reducing our consumption of energy in favor of more efficient solutions in heating, lighting, air conditioning, and hundreds of other important arenas of energy generation and consumption is far easier to achieve with efficiency than other means. In particular, efficiency solutions offer far more appealing returns on investment than even the most sexy, new-age modalities of renewable energy, smart grid, electric transportation, energy storage, etc.

As suggested above, the real problem with the widespread adoption of efficiency is often its profound lack of sex appeal. Even solar PV itself is not horribly exciting to look at, and, sadly, this often functions as a stumbling block to its acceptance into our society. I’m reminded of my colleague John Perlin, scholar-in-residence in the physics department at the University of California at Santa Barbara. In addition to his many other duties at UCSB, John is responsible for providing public tours to those who are interested to see the PV arrays that UCSB has deployed to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels. John often laments that he will show off all this magnificent work, only to have someone ask: “Is that all there is? Where are the moving parts? Doesn’t it make any noise?”

In any case, let us never discount the importance of the so-called “negawatt,” that is, the watt of electrical power that is never produced and consumed.

In closing, a colleague of mine in England asked me to include into this discussion a mention of his very favorite product in the vast and ever-growing LED space. That’s AuroraGlow’s Colour Changing LED bulb. I have to admit that it’s a cool one.

From the article:

“Energy efficiency remains far and away the greatest opportunity for us to stem the rise of greenhouse gases and toxins into our atmosphere.”

That is highly questionable even though it is worthwhile to pursue energy efficiency.

In theory, getting all of our power from non-CO2 emitting sources could reduce CO2 emissions from power sources to zero. Accomplishing the same thing by increasing energy efficiency would require increasing efficiency to the point that no power would be required which obviously is impossible. We could not have lighting, electric motors, etc., that use no power.

LED lighting has recently, because of price reductions and efficiency increases, become competitive with fluorescent and other lighting sources. Therefore, as I use up my inventory of fluorescent tubes and CFL, I will probably replace them with LEDs PROVIDED THAT reasonable replacements become available for fluorescent tubes.

Regarding the energy efficiency of LEDs, the most efficient LED chips in commercial use deliver around 150 lumens per watt of white light – which allowing for some losses in the driver (Power electronics controling the LED) gives slightly over 130 lm/w off the circuit.

Some lab LEDs have exceeded 200 lm/w and it seems likely that we will approach 200 lm/circuit watt in the next few years.

Re suitable LEDs for fluorescent tube replacement, these are now widely available – it just takes a few minutes to bypass the fluorescent ballast. Typically such LED tubes have a row of LEDs along an aluminium heat sink, and a milky cover – so that it becomes very difficult to tell the difference between an LED and fluorescent tube when looked at from below.

If replacing typical suspended ceiling office fittings, I would suggest replacing the whole fitting with a back lit LED panel for an even light with a smooth wipe clean surface – this gives far superior luminare performance with less light lost in the fitting and a better appearance. (Back lit perform better than the thinner side lit panels in terms of lm/w and in terms of long term retention of performance better optical performance and heat sinking). A 40W LED panel 600mm x 600mm can replace 2 x the same size fluorescent fittings with 4 tubes each – replacing around 170W with 40W whilst achieving similar useful light output.

Still, efficiency cannot be understated. After all, every watt we don’t use is a watt we don’t have to buy equipment to generate or store. Efficiency is always the first place to start and the biggest bang for the buck.

Exactly. Thank you.